Wednesday, August 4, 2010

How to Measure Throughput For ICD (Inland Container Depots) & CFS (Container Freight Stations)

they pass through the terminal. The different operations involving movements of containers should be measured to consider overall ICD/CFS throughput:

-Railhead/berth transfer throughput

-Container yard throughput

-Receipt/delivery throughput

-Gatehouse throughput

Each of these is expressed as container moves per unit time. The sum of these yields the depot throughput. The striking result of this measure is that a given volume of container traffic corresponds to several times that number of container movements. This information is crucial for such tasks as resource allocation requirements and determining handling costs for containers.

Railhead or berth transfer throughput is a measure of the number of container moves between the railhead or berth and the container yard. The calculation includes all the inbound and outbound containers and any shifts and restows that occur at the transfer location. This data is extracted from loading and discharge sequence sheets.

Container yard throughput represents the total number of movements that take place in the container yard. This measure includes stacking of inbound containers and inbound shifts and restows, unstacking of outbound containers and return of shifts and restows, movements of full and empty containers to and from the CFS, movements to and from customs, health and other examination areas and in-stack movement of containers. If the terminal operates lift-truck system, stacking and unstacking movements are not counted, as they are included in the railhead/berth transfer throughput measure. This measure is useful in providing managers and supervisors with information on in-stack movements, which are considered unproductive.

Receipt/delivery throughput measures the activity relating to the receipt of outbound containers at the depot and delivery of inbound containers from the depot. The activities to be included in the ICD throughput calculation are those that involve the movements between the container yard stacks and the interchange locations and the stacking/unstacking of containers associated with those movements.

The remaining activities are related to gate activities and so are included in a gatehouse throughput measure, which measures the number of vehicles handled. The gatehouse throughput measure is not included in the ICD throughput calculation because the nature of the activities undertaken at the gatehouse is different from those activities associated with the other terminal operations – gatehouse activities do not involve ICD handling equipment.

Detailed info if needed contact me in person at ashokmishra1@gmail.com

Thanks & Regards

Ashok Mishra

Friday, July 30, 2010

Introduction to UNESCAP Time/Cost - Distance Methodology

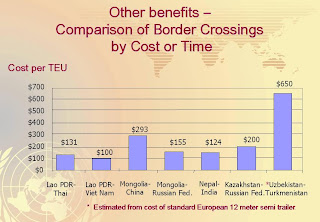

The UNESCAP “Time/Cost - Distance Methodology” is a practical and simple way of illustrating the time and costs involved in the transportation process.

How you can use the UNESCAP “Time/Cost - Distance Methodology”

A basic version that does not require an upfront estimate or quotation for the overall transport costs It provides with a quick analysis of time and cost distribution along your route.

The advanced version accommodates the analysis of long routes with many stops and allows for the analysis of time/cost intensity of individual activities at stops.

Data can be an initial estimate by a freight forwarder or transport operator for an individual consignment or, even an average figure. Once the data is entered into either of the T/C –D templates graphs comparing time over distance and cost over distance will be automatically produced. You may even experiment with the templates using hypothetical data as given in the example to familiarize yourself with the functionalities of the methodology.

It is best to look at one route or one particular shipment of goods. The minimum information needed is route, mode and distance plus either time or cost.

To enter the data correctly, please follow the 5 basic steps: -

Step 1: Establish the route you are going to examine i.e. A to B via C and D (or as in the below example in Figure 3 we have used Tianjin to Ulaanbaatar via the Erenhot and Zamyn Uud border).

Step 2: Ascertain what modes of transport are being used on your route (e.g. Road/Rail)

Step 3: Determine the distances between all the points (e.g. Tianjin to Erenhot = 983Km).

Step 4: Check how long it takes for the goods to reach each point (e.g. Tianjin to Erenhot = 29 hrs. 12min.).Step 5: Ascertain how much of the total cost is taken up by each leg of the journey, modal transfer, border crossing or other cost/tolls that are encountered. (e.g. Tianjin to Erenhot = $500).

What is Piggyback in Transportation

The goods are packed in trailers and hauled by tractors to the railway station. At the station, the trailers are moved onto railway flat cars and the transport tractors, which stay behind, be then disconnected. At destination, tractors again haul the trailers to the warehouses of the consignee.

Picture Source :Google Image

This is a system of unitised multimodal land transportation, a combination of transport by road and rail. It has become popular in Latin American and European countries because it combines the speed and reliability of rail on long hauls with the door-to-door flexibility of road transport for collection and delivery.

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Why an Unknown Shipper Indentification Introduced in Transportation ?

- An Unknown Shipper is a company or individual who:

•is a new customer, has not previously traded with Forwarder

•has no name and address details (NAD)

•has no account number recorded in Forwarders computer system

•is known shipper who has previously traded with Forwarder but is requesting a collection from an unknown company address

•a guest at a hotel even if the hotel has an account number with Forwarder

•is an ‘unregulated’ third party transport company

•is delivering a consignment into Forwarder depot

Why is it important to identify Unknown Shippers?

• Forwarder needs to identify Unknown Shippers to protect their customers and self interests.

• Forwarder do this by:

•inspecting the goods of those customers who are not familiar with what can be transported by Forwarder or what the legal requirements are for Transportation

•ensuring consignments carried by Forwarder do not affect safety and must not unnecessarily cause delays to other shipments

•preventing any category of prohibited goods entering Forwarder’s handling networks

•complying to Civil Aviation regulations and local legislation

What led to the change of the procedures?

•11th of September 2001 terrorist attacks in USA caused increased focus on security by all transportation companies of the World

•laws for transporting goods by air , sea and road are adjusted and have become more strict

•a number of cases in which Unknown Shippers were not identified correctly and goods were not inspected

•dependency of a manual process to identify Unknown Shippers with a risk of non compliance

•possibility to link current Forwarders systems and to automate a large part of the manual processes for Security Reasons

Thats how new categories of Unknown Shippers Born !!!! :)

Monday, May 3, 2010

A Checklist of Trucking Considerations

The Ocean Bill of Lading

The Ocean Bill of Lading

The Ocean Bill of Lading (OB/L) is evidence of the delivery of goods to the carrier as

well as constituting a contract of carriage between the shipper and the ocean freight

carrier.

The Ocean Bill of Lading, when fully executed, constitutes the actual deed to the goods

being shipped and is an official "document of title". Essentially, this means that the

Ocean Bill of Lading can be used to meet banking requirements in issuing letters of credit

as the bank may use this document to retain control over the merchandise.

Three Originals: Ocean Bills of Lading are traditionally completed with three signed

originals being issued. These are distributed as follows:

2 copies are forwarded to the Consignee under separate cover

The Shipper as a back-up document retains 1 copy

The consignee surrenders one original B/L to the Ocean Carrier at final destination in

order to effect release of the shipment. There are three possible instructions on an O B/L depending on how the goods are to be transferred from shipper to consignee for the shipment:

Straight Bill of Lading: States the Consignee's actual name, meaning that the when

the consignee or its agent present any one of the original bills of lading, the carrier must deliver the shipment into the consignee's possession.

"To Order" Bill of Lading: Consigns the goods to the shipper, title of the goods only

being transferred through the shipper's (or in some cases, the bank's) endorsement by stamp or signature. Once this O B/L is properly endorsed, the holder or named party

becomes owner of the goods.

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Problems in Container Terminals

This Post describes problems in container terminals. The main functions of these terminals are delivering containers to consignees and receiving containers from shippers, loading containers onto and unloading containers from vessels and storing containers temporarily to account either for efficiency of the equipment or for the difference in arrival times of the sea and land carriers. Containers are usually handled in two important compartments. We shall first describe what the compartments are, including the equipment involved in them. Then, the operations in container terminal are disclosed. After that, main decisions in the container terminal are defined. These decisions are subdivided into five scheduling problems.

Compartments

The first compartment is Yard-Side, which sometimes is referred to as Storage Area or Stacking Lane . In any container terminal, storage yard serves as temporary buffers for inbound and outbound containers. Inbound containers are brought in the port by vessels for import into land, whereas outbound containers are brought in by trucks and for loading onto vessels in order to export. A large scale yard may comprise a number of areas called zones . In each zone, containers are stacked side by side and on top of one another to form rectangular shape, which is called block

There is expensive equipment in the storage area for container handling, which is referred to as Rubber Tyred Gantry Cranes (RTGCs) . A RTGC can be seen across the block from the front-left to the front-right, while it is unloading a container from a truck. The efficiency of yard operations often depends on productivity of these RTGCs and their deployment. To balance the workload among blocks, RTGCs are sometimes moved between blocks so that they can be fully utilized.

To move between blocks , an RTGC has to make a 90-degree rotation (of its wheels) twice to move from one block to another. Since RTGCs are big in size and slow in motion, their movements demand a large amount of road space in the terminal for a non-trivial time period. Furthermore, any RTGC movement from one block to another takes time, and will result a loss in productivity of the RTGC.

The second compartment in the container terminal is Quay-Side. Usually, Quay-Side consists of a limited number of berths, each of which is equipped by several Quay Cranes (QC). The cranes are used to unload containers from vessels of the wharf and load containers to vessels. The cranes are usually flexible to be moved from a berth to another. A Typical QC, while it is unloading containers from a vessel to put it down on the truck in order to transport to the storage area.

Berths are essential resources in the container terminal. Therefore, with a high traffic of vessels, it would be ideal to have optimal allocation of berths to vessel to prevent undue delays of vessel in the terminal. At any time, only one ship can be docked at a berth.

Operations

The main operations in the port start by ship’s arrival. After a ship is berthed, it invokes a number of delivery requests for discharging. There are some vehicles in a terminal, which are usually Automated Guided Vehicles (AGV), or Internal Trucks (IT) Idle vehicles are dispatched according to the unloading request list to deliver containers from the berth to designated places in the storage yard. The QCs first unload containers from the containership and put them onto the vehicles. After that the vehicles carry the containers to designated storage area blocks and RTGCs unload the containers from the vehicles. Then the containers are put onto the yard stacks. In some terminals there is a number of Straddle Carrier, capable of loading, transporting and unloading of containers.

After the unloading phase of the ship, the loading phase will begin. On the landside, eXternal Truck (XT)brings in outbound containers before loading process of the relevant vessel, and they pick up inbound containers from the storage area or from the discharged vessel by QCs. The ship issues a number of loading requests. Vehicles are dispatched corresponding to the loading request list to deliver containers to the QCs. The operation is the reverse of the unloading process.

There are two major types of waiting lists in the port. The first one related to vehicles while the second one dedicated to the cranes. A vehicle has to wait if it has arrived at the crane's location but the crane is busy with other vehicles. A QC has to wait for a vehicle if it is ready to put a container onto a vehicle or to pick up a container from a vehicle but the vehicle has not arrived on the quay-side. Usually the cranes waiting time is more critical than the vehicle waiting time for efficiency of the terminal operations. Any delay in a quay crane operation will cause the same amount of time delay in all subsequent operations assigned to the same quay crane. This delay may even affect the ship's stay at the berth. Usually every ship has a time window and any delay lead to growing costs for the terminal. So one of the most important decisions in this system is allocation of quay cranes so that satisfy ship-timing window or minimize waiting times of the ships in the port.